For the last three weeks, the beaches of Thiruvananthapuram have taken on a strange shimmer.

That shimmer, barely visible from a distance, comes from millions of plastic nurdles—tiny white pellets, each just two to three millimeters wide—that have washed ashore after a cargo ship sank off Kerala’s coast on May 25.

The Liberia-flagged MSC ELSA 3 sank 14 nautical miles off the coast with 643 containers on board. About 70 held nurdles, and 13 carried calcium carbide — a chemical that creates flammable gas when it contacts seawater.

The Indian Navy rescued all 24 foreign crew. But the cargo did not survive.

Over 60 containers, many empty, have drifted ashore. Others remain submerged or lost at sea.

Fire and Hazardous Cargo Aboard Second Ship

Fifteen days later, another cargo ship, the MV Wan Hai 503, caught fire 44 nautical miles off Azheekal in northern Kerala. It carried 1,754 containers, 143 of which were packed with dangerous goods—substances like naphthalene, trichlorobenzene, pesticides, and flammable solids.

Eighteen of the 22 crew were rescued. Four remain missing.

The sunken vessel continues to raise alarms, with possible chemical leaks putting ocean health and coastal economies at risk.

Efforts to Clean Spill Begin — Challenges Persist

Local authorities and a salvage company have started cleanup operations in coastal areas like Chirayankeezh.

“We’ve already collected about 500 sacks of nurdles from our panchayat beaches,” said M Abdul Wahid, the local council president. “There are still tons left. It’ll take time.”

A report from the Directorate General of Shipping on June 25 confirmed that 18.5 metric tonnes of nurdles had been secured at a warehouse in Kollam. More pellets and packaging material are expected to wash up in the coming weeks.

Experts Warn of Deep Marine Impact

Marine scientists are raising alarms about the slow-moving but dangerous effects of the pollution.

Professor Anu Gopinath of KUFOS explained that nurdles, initially floating, will eventually sink and enter the food chain. Fish will consume them. And so will we.

She also warned that if containers with hazardous chemicals have leaked, marine life—especially during its breeding season—could suffer lasting damage.

Another marine biologist, Professor VN Sanjeevan, studied mackerel eggs off Kollam. About 70% were found damaged. He suspects chemical shifts in seawater pH are to blame.

Currents may carry these contaminants toward the Gulf of Mannar, a rich ecological zone and biosphere reserve.

Fisheries Sector Already Feeling the Strain

Fishermen in the state say they are paying the price. Workdays lost, nets destroyed, and widespread uncertainty.

“This is peak breeding season, and we’ve been kept away from the area around the Quilon Bank,” said Charles George, president of Kerala Matsya Thozhilali Aikya Vedi.

He added that fishing equipment worth lakhs has been damaged by drifting containers. “The compensation—just ₹1,000 per family and some rations—is not even close to enough.”

George plans to petition the high court for an independent probe into the ecological damage.

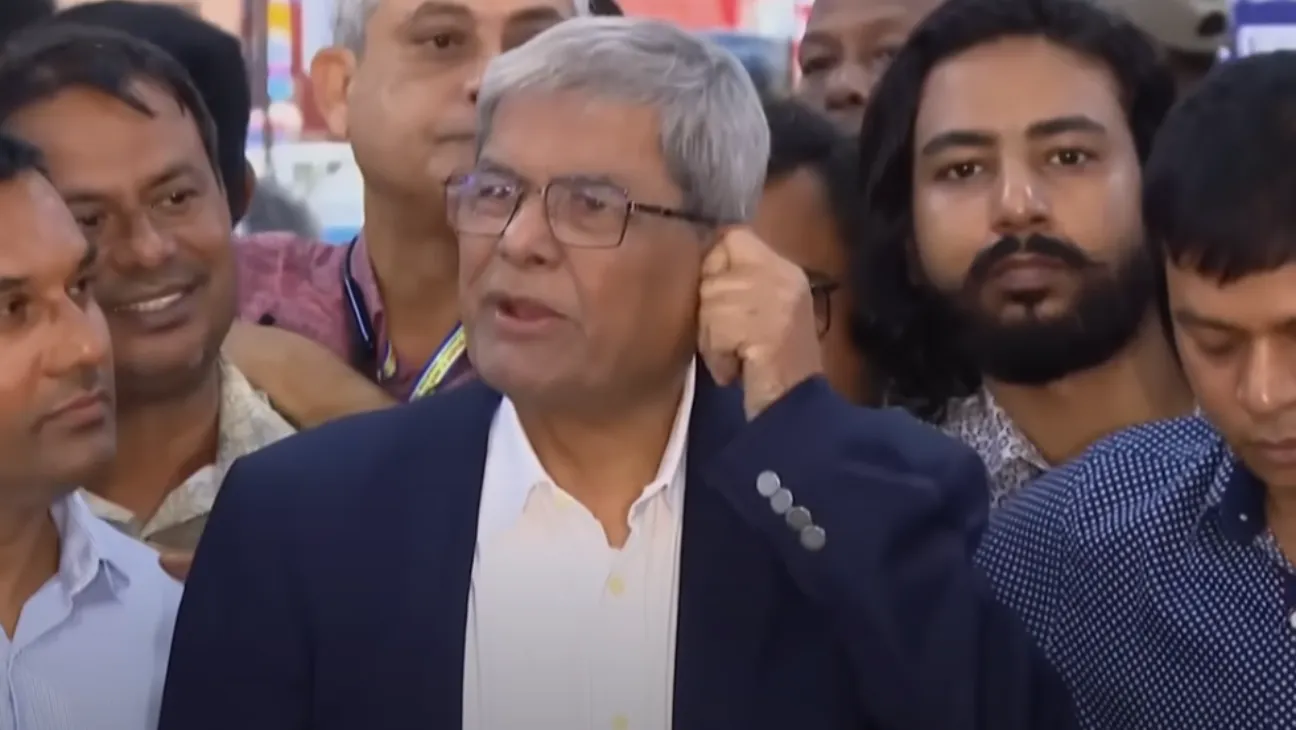

Questions Raised About Government and Regulatory Bodies

Many are now questioning the response from the state government and its agencies.

Environmentalists say the government has no functioning marine pollution protocol, despite years of planning. A proposed system from 2015–16 was never implemented.

“The Pollution Control Board said these nurdles were harmless. They weren’t prepared. They didn’t act. That’s the reality,” said Sridhar Ramakrishnan, an environmental observer.

Harish Vasudevan, an environmental lawyer, called the state’s pollution board a “white elephant.”

On May 29, state officials said they wouldn’t press charges against MSC, calling it a “reputed company” that supports the Vizhinjam port project. An FIR was filed two weeks later.

By then, the damage had begun.

What Now?

As cleanup crews work to scoop plastic pellets from the sand and scientists monitor fish eggs and water samples, one thing is clear. Kerala wasn’t ready.

And the cost may keep surfacing, one tide at a time.