Iran has warned it will prevent the creation of a new U.S.-backed transport corridor in the South Caucasus, a project central to a peace plan between Azerbaijan and Armenia announced in Washington.

The Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity, known as TRIPP, would run across southern Armenia, giving Azerbaijan a direct link to its exclave of Nakhchivan and on to Turkey. Under the plan, the U.S. would hold exclusive development rights to the route, which the White House says could boost energy exports and other trade.

On Saturday, Iran set a distinct limit which drew the ire from the region. Ali Velayati, who serves as a senior advisor to the supreme leader, voiced Tehran’s readiness to, “block the corridor.” Velayati branded the project ‘provocation’ that if allowed to progress, would ‘bring the whole region to chaos.’

He pointed to recent military drills in northwest Iran as proof of the country’s resolve. “This corridor will not become a passage owned by Trump, but rather a graveyard for Trump’s mercenaries,” Velayati told Iranian media.

Iran’s foreign ministry had earlier described the peace agreement as a positive step but warned against foreign intervention near its borders. Analysts say Iran, under pressure over its nuclear program and facing the aftermath of a short war with Israel in June, may not have the military capacity to stop the project outright.

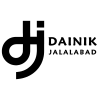

The corridor scheme was disclosed during the meeting at the White House, former U.S. president Donald Trump welcomed both Ilham Aliyev, the President of Azerbaijan, and Nikol Pashinyan, the Prime Minister of Armenia. During the meeting, the two leaders signed a joint declaration, which Trump mentioned could potentially lead towards a conclusive agreement after years of strife.

The agreement was notably reached without the participation of Russia, who has been a historical influencer of the balance of power in the South Caucasus and a longtime supporter of Armenia. Moscow, asserting its role as the region’s guardian, positioned itself as supportive of peace but insisted that solutions be confined to the region, cautioning against reproducing what it termed the Western blunders of Middle Eastern diplomacy.

Turkey, a close ally of Azerbaijan and a NATO member, welcomed the accord. Azerbaijani officials have framed the TRIPP corridor as a turning point. “The chapter of enmity is closed and now we’re moving towards lasting peace,” said Elin Suleymanov, Azerbaijan’s ambassador to Britain. He said a final deal could be signed quickly once Armenia removes a constitutional reference to Nagorno-Karabakh, the disputed region over which the two countries have fought since the late 1980s.

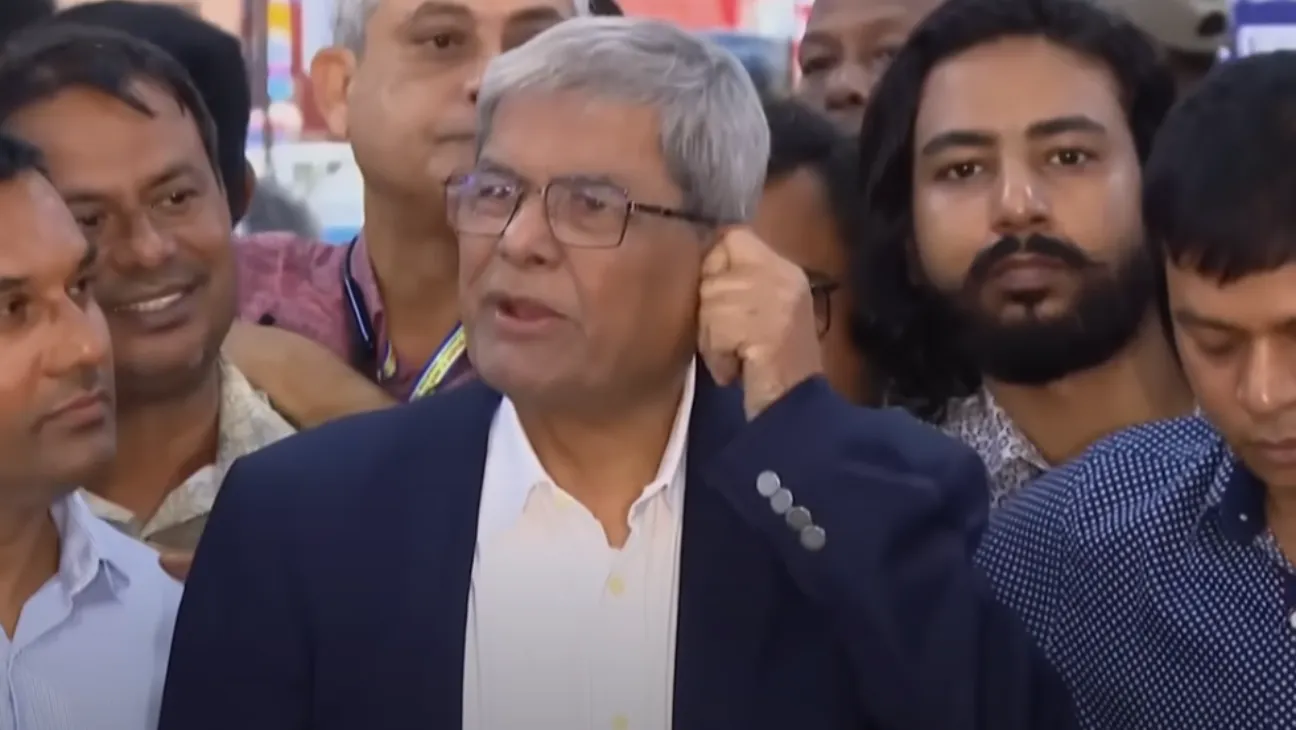

The Prime Minister of Armenia has suggested holding a referendum to adjust the Constitution, although the date has not been released. In the meantime, the date for the national elections has been set for June 2026, by which time it is hoped the new Constitution will be finalized.

Many events unfolded in 2023, however. It marked the year Azerbaijan fully gained control over Nagorno-Karabakh which marked the end to a long-standing dispute. What followed, however, was the humanitarian tragedy of the region’s largely ethnic Armenian population having to abandon their homes to escape to safer havens in Armenia.

While the White House presented the TRIPP agreement as a breakthrough, experts warned of unresolved issues. Joshua Kucera of the International Crisis Group said the plan leaves key questions unanswered, including customs arrangements, security, and Armenia’s reciprocal access to Azerbaijani territory. “These could be serious stumbling blocks,” he said.

Suleymanov dismissed concerns about Russia’s exclusion, saying the project could benefit any country that chose to participate. Whether Iran will act on its threat to block it is another question — and one that could decide whether the deal survives the months ahead.