Bholaganj’s Sadapathor quarry, once a sought-after landmark in Sylhet topography, now hosts a systematic extraction campaign that, according to community members, is fast exhausting its ironical signature white stone deposits.

Witness reports implicate a coordinated cartel whose reach extends to influentials in the magistracy and, reportedly, pockets of uniformed guardians. Over the past quadrimester, villagers assert that operations have migrated from the cover of night to the noontide glare, pursued openly past watchtowers whose occupants discharge little more than indifference.

Abdul Qadir, a fixture in the regional census for four generations, remembered a riparian economy in which quarried columns rarely exceeded the value of boatmen’s wages. “Theft now records its rise in daylight’s currency. I compute losses in crores of taka. I compute extinction, for the white faces of the hills are disappearing.”

The escalatory vector tracked its origin to the hour the Awami League Ministry renounced its mandate on 5 August 2024. Temporary deployments of the armed battalions and street protests acted as an intermission to the overt lifting, yet spectator reports insist that night registries resumed when civil watch layers demounted. Storage basins already catalogued to the magistracy are, villagers assert, protected by both named and nameless spectators, permitting merchandise to transit without Lagudi and without levy.

During a transect of the freshet, hydraulic equipment and labour battalions were sighted extracting marble members directly from the river’s substrate. Estimators from the field now assign a daily mobilization of 4,000 to 5,000 operatives, an alien cadre that overtops the home census. Reinforcements are ferried from Sunamganj and Habiganj, moving in single-article skiffs along the Dhalai under the frontal courtesy of hire-string sirdars who pay half-wages for protection against the stream and against the watch.

Kawsar, who works from Sunamganj, reported he averages three to four trips daily, earning between Tk2,500 and Tk2,600 for each one. “Occasionally BGB and police chase the convoys, but we number in the thousands. They can’t apprehend us all,” he remarked. Rough stones are bartered on either riverbank before being freighted across the country. When raids do occur, crews stop for a few minutes, then carry on as before, he noted.

Kawsar also highlighted a different danger: cargo vessels filled with stones that move under darkness could collide with the Dhalai Bridge, resulting in a catastrophic event.

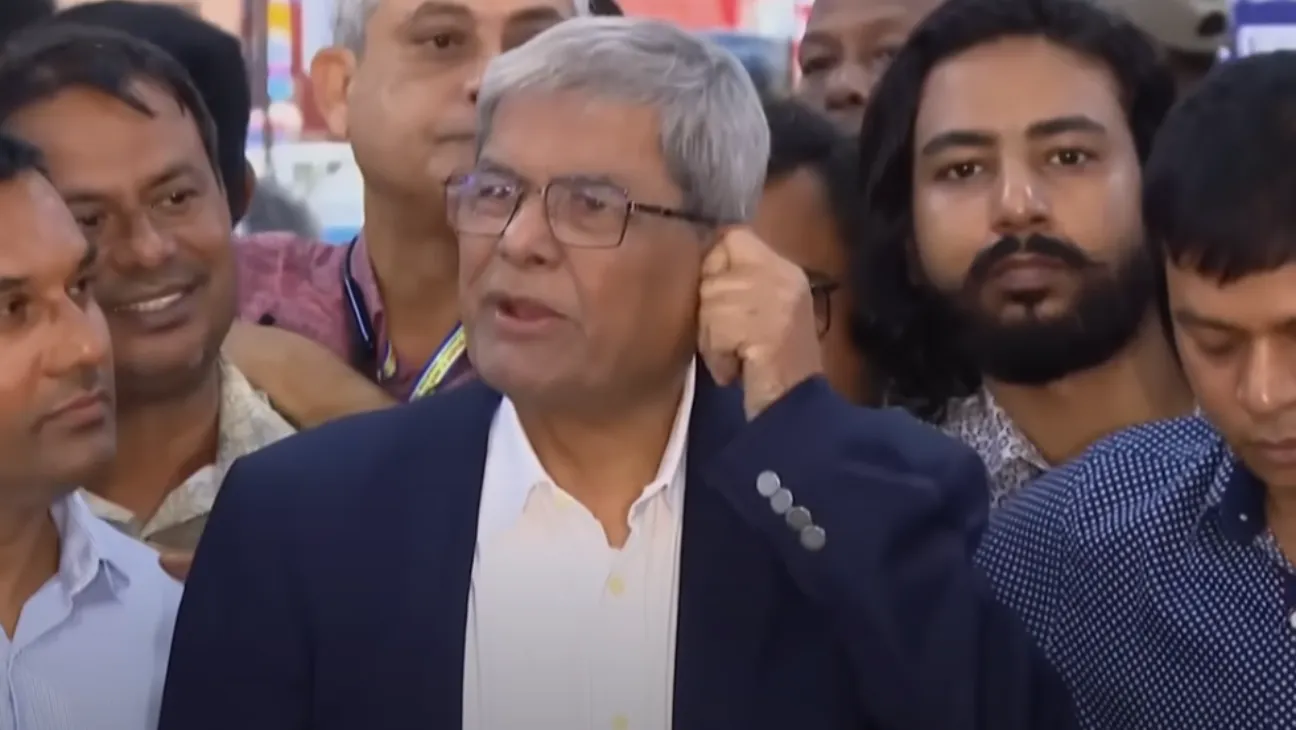

Advocates for the environment interpret the situation as symptomatic of state apathy. “The administration has never adopted measures that indicate a genuine will to safeguard the white boulders. A year ago, the very idea of disturbance was unthinkable,” stated Advocate Shah Shaheda Akhtar, the Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association’s Sylhet coordinator.

Officials contend that they are responding, yet rogue activity persists. Sylhet’s Deputy Commissioner and District Magistrate, Muhammad Sher Mahbub Murad, stated that raids continue, yet the extractions advance. Companiganj’s Upazila Nirbahi Officer, Azizunnahar, reported a four-and-a-half-hour operation this week and four additional raids in the past week, but acknowledged that mobile courts cannot be stationed in every location at all times.

The quarry is poised at an ambiguous juncture. For the rural population, the projected closure signals more than a marginal contraction of income; it erodes the composite character of a terrain that has structured their memories and daily routes since childhood.