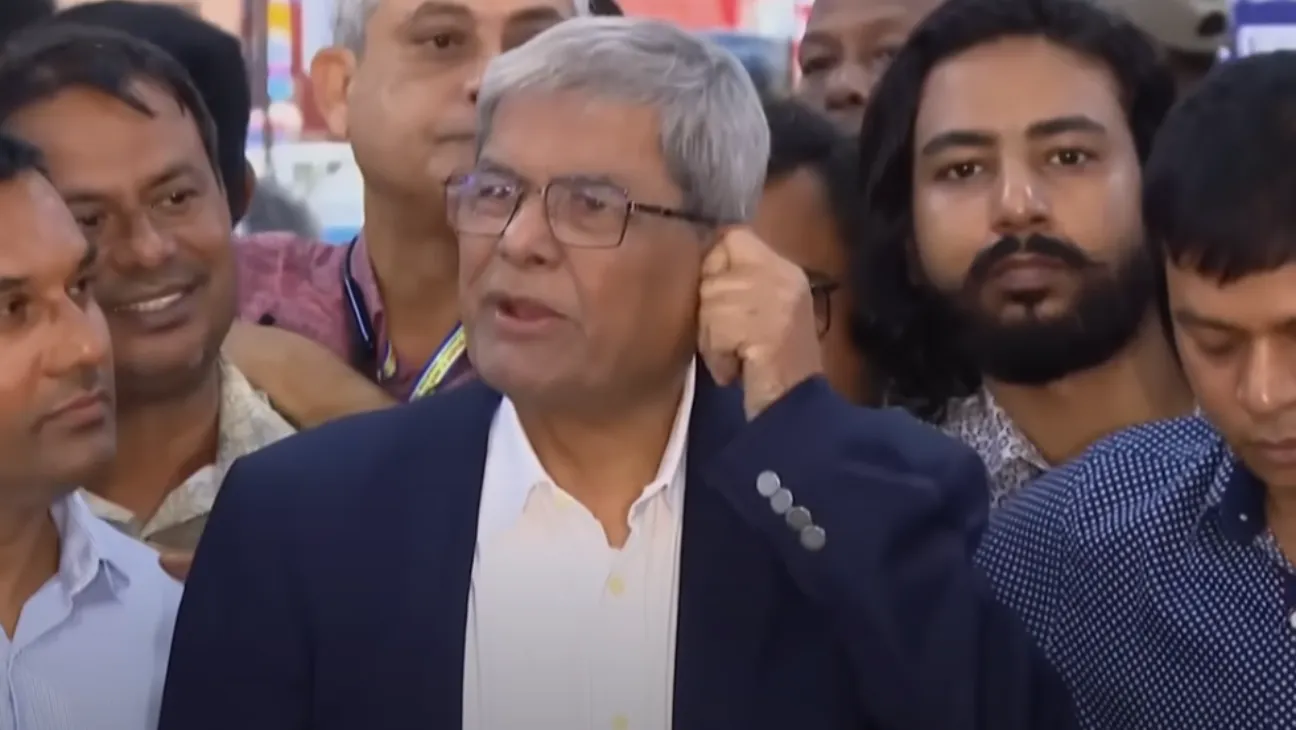

At a budget seminar in Dhaka on Saturday, Energy Advisor Muhammad Fouzul Kabir Khan made pointed remarks about the deep-rooted presence of corruption across Bangladesh’s political and bureaucratic sectors.

Speaking at the SIRDAP auditorium, Khan said the problem isn’t just political. It cuts through every layer of influence.

“Politicians, bureaucrats, professors—no one wants corruption to end,” he said. “They all just want a turn.”

Khan shared that even in his own office, politicians meet with him regularly, but the conversation never touches on eliminating corruption. Instead, he claimed they ask for access.

“They say, ‘You know how it was under the last regime. We couldn’t do business. Now please let us in,’” he added.

He described a pattern that has become normalized. “People don’t want change. They want a chance to benefit.”

An Example from the Field

Khan pointed to a recent situation within the Bridges Division.

While constructing housing for displaced residents, officials allegedly identified extra space and proposed allocating it to government employees—even though housing is not part of their mandate.

“There’s a separate ministry for housing. Still, top officials, including cabinet secretaries and university teachers, accepted the benefit,” Khan said.

To him, this reflects a deeper problem. Corruption isn’t isolated. It’s systemic.

A Push for Open Competition

Khan stressed that his team is trying to move in a different direction—one centered on transparency and competition.

“We’re working to build competition in the economy,” he said. “Anyone who wants to do business should have a fair shot.”

He described changes to the way power projects are awarded. Previously, such projects were negotiated privately. That has now stopped, he said.

“We canceled that system. Now all projects go through open tenders,” Khan explained. “No more private discussions. No more handpicking.”

The move hasn’t been popular.

“Everyone hates this. I won’t name names. But trust me, they all preferred the old system,” he said.

Real Impact on Public Spending

One reform, Khan said, had a major effect.

In fuel procurement, a requirement was removed that forced suppliers to own a refinery. Once lifted, the number of competitors increased from four to twelve.

More competition brought better pricing.

He said the premium on fuel imports dropped by 35 cents per unit. Over a year, that translated into savings of 15 billion taka.

“That’s the benefit of competition. The people win,” he added.

But despite the savings, he acknowledged strong pushback.

“People don’t like competition. They say it ruins their chance,” Khan said.

Where Things Stand

With unusual honesty, Khan shed light on the uphill battle against entrenched corruption in Bangladesh.

His comments reflect hope for change, but also frustration with a power structure many are unwilling to abandon.

The question now is whether reforms based on transparency can continue—or whether internal resistance will pull things back.