The question of when Bangladesh’s next general election will be held—December or June—has started to fade from public focus.

A new question has taken its place: how should the election be conducted?

So, here’s a huge question bubbling up in politics right now: Should Bangladesh change the way it votes? The system now is simple: winner takes all. But a lot of people are pushing for something different, where the number of votes a party gets actually matches the number of seats they win.

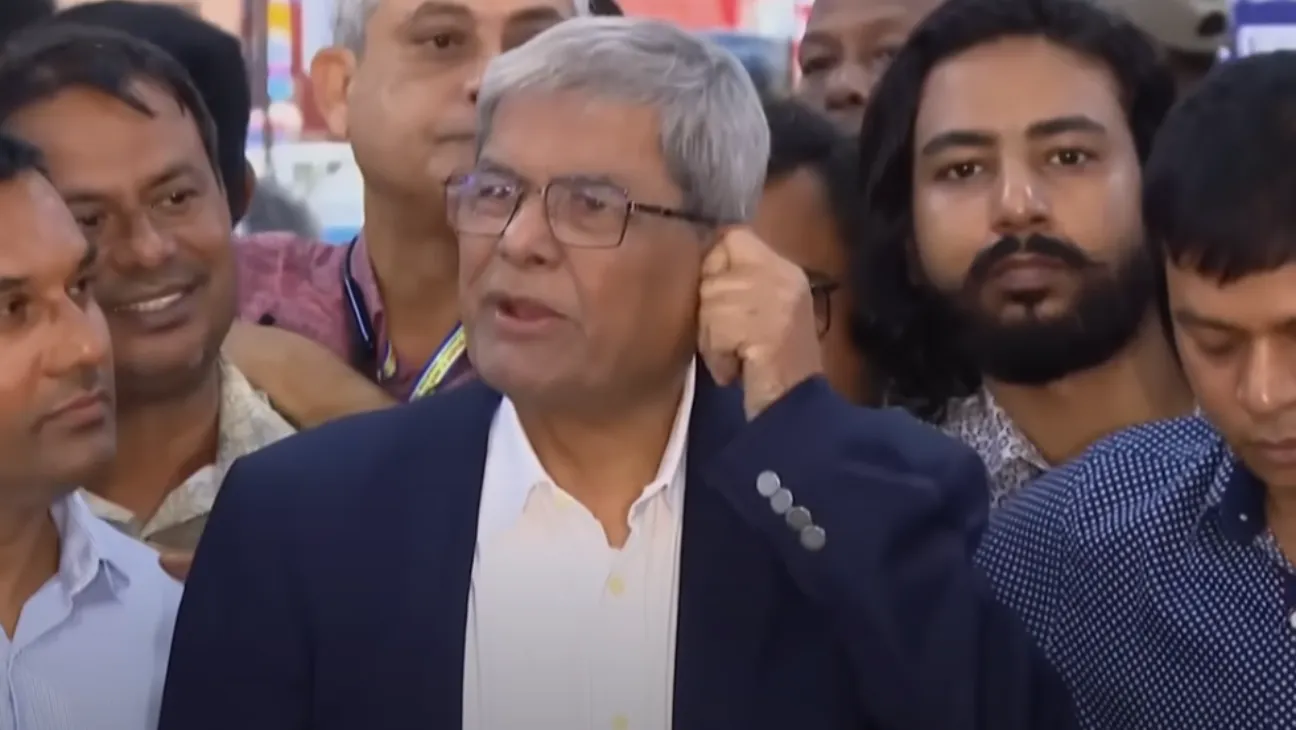

This isn’t just an academic debate anymore—it really took off after a rally in Dhaka on June 28, when a handful of smaller parties made it clear they want the system changed.

What Is Proportional Representation?

For many voters, this is unfamiliar territory.

Imagine a party in Bangladesh wins 10% of the total vote. Under a PR system, that means they get 30 seats in Parliament. Simple as that. It wouldn’t matter if they lost every single local race; their national vote share guarantees them a spot.

The whole point is to make the Parliament a mirror of what the entire country voted for. That’s why it’s so common—91 out of 170 democracies use some form of it.

Smaller parties see this as an opportunity. They rarely win individual constituencies, but a nationwide 1 percent vote under PR could still land them three seats.

Why Smaller Parties Want the Change

Parties like Jamaat-e-Islami, the National Citizens’ Party, and Gono Odhikar Parishad have all spoken in favor of proportional representation.

For them, the appeal is simple: it removes dependence on larger party coalitions.

In Bangladesh’s traditional system, smaller groups often need to join alliances with major parties like the Awami League or BNP just to participate meaningfully.

PR would give them a direct path to parliamentary presence, even without formal alliances.

They could run independently and still gain influence.

Resistance From Major Political Players

Larger parties, especially the BNP, are less enthusiastic.

They argue that elected representatives should come from direct contests in individual constituencies. That’s how you test local popularity, they say.

Under PR, a party could have zero direct wins but still enter Parliament with dozens of seats.

This, BNP leaders believe, undermines electoral accountability and local engagement.

The concern is also strategic. Major parties have long dominated Bangladeshi elections. PR would likely chip away at that control.

Could This Shift Reshape Bangladesh’s Parliament?

There’s potential for real change.

Think about it: our Parliaments are almost always run by just one or two big parties. The downside, according to critics, is that it pretty much kills any room for disagreement or negotiation.

Those who want PR say it’s the answer to this problem, arguing it would create a more balanced and representative government.

With more parties represented, especially opposition voices, the legislative process could become more balanced.

Some even suggest that opposition MPs could collectively block laws or bills that don’t serve the public interest.

That kind of pushback is rare under the current system.

What’s Next?

The discussion is far from settled.

For now, the Election Commission has not made any move to change the existing model.

But the pressure from smaller parties is building. And the public—many of whom are still learning what PR actually means—is starting to ask more questions.

Can a fairer distribution of seats help improve representation? Or would it make governance more chaotic?

That’s the next big political question facing the country.